Photo by Steven Koress

Vince Lawrence, 46, has always been content to work behind the scenes, yet his ideas and hard work shaped the history of music. He is responsible for many firsts, from the first house record (“On and On” with Jesse Saunders) to the first major label (Trax) to the first house track on the Billboard charts (“Funk You Up,” also with Jesse). Lawrence built his early success into a music industry career, earning numerous gold and platinum awards in the process. I interviewed him in the control room at Slang Musicgroup, Chicago on January 9, 2010.

Jacob: What part of Chicago did you grow up in?

Vince: I am originally a South Sider. I lived all over the South Side. I lived in Roseland, Jeffrey Manor, South Shore, Hyde Park, Lake Meadows, Beverly…. I lived on Lakeshore Drive for a little while. Quickly moved to Diversey and Ashland and then Humboldt Park… then West Loop, now here. I’ve lived all over Chicago. I’m a Chicagoan, in a real sense.

I understand your father was in the music business?

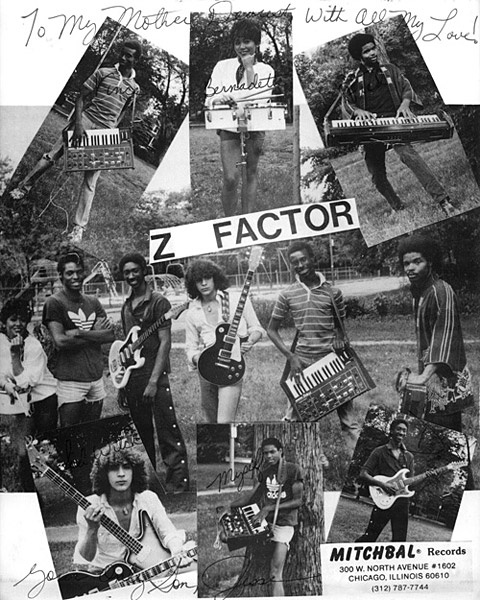

Yes, my father worked with Eddie Thomas, who was Curtis Mayfield’s partner in Curtom records. He had a small blues and R&B label of his own [Mitchbal Records]. Around the time I was fifteen or sixteen he wanted to show me the record-making process, so I made a record as part of it…. That was “Fast Cars.” And I was really fond of that record. I guess if you’re sixteen and you make a record, you’re going to be fond of it. I really wanted to capture the essence of the parties I was going to… First Impressions, The Loft, ultimately The Playground and The Rink. There were parties all over the place.

What were some of your musical influences?

I had a really eclectic record collection, and I would say thanks to the Columbia Music House or something like that. Let’s see, double albums: I had Stevie Wonder Songs In The Key of Life. Obviously. Electric Light Orchestra Out of the Blue. Not so obvious. Michael Jackson Off the Wall. Kiss Destroyer. A lot of the New Wave records we were listening to at the parties, you couldn’t get those at the Columbia Record Club, but I listened to everything.

I listened to rock records, pop records, R&B records, funk records—Parliament-Funkadelic “Aqua Boogie” and things like that—and really became fascinated with these records that were made with synthesizers. I’d gotten my own synthesizer from work that I did ushering people to their seats at ball games and concerts and I was really focused on recognizing synthesis that was going on in modern music at the time. I thought it was great when you could make a record with all synthesizers.

What was your first synthesizer?

It was a Moog Prodigy.

Do you still have it?

No, I don’t. It was stolen from me a couple years after I had it. I was really fond of it, though.

Tell me more about “Fast Cars.”

Well, the session happened after my dad says, “Hey, we’re going to make a record,” and I said, “Great, this is cool.” I very quickly put together a band [Z-Factor] to support my synthesizer playing and wrote this song. We were really excited because the day we were going to go in the studio, we knew about it about three weeks ahead of time, so by the time we got there we were really pumped up and a record that we rehearsed at probably 120, 123 BPM got recorded at 142.

How many copies did you press?

I think initially that we pressed 1000, but we sold those very quickly and ended up pressing 3 or 4000 more. My dad could tell you how many we sold. We got the record on the radio…. WGCI and WBMX, primarily. It was just a wonderful thing to hear your song on the radio.

Were you the first local guy with a dance record at that time?

I wouldn’t say that I was the first local guy, because a couple of years before, I asked my Dad to go to summer camp and we really couldn’t afford it, so he sent me on the road with a guy by the name of Captain Sky, and he had a record. He had a big fucking record. And I have to say that Daryl’s existence was a real indicator to me that there was something that I could do. I could see a tangible result of the effort to make music and get out there. Because Daryl had a record “Wonder Worm” that was a smash all over Chicago, and he had previously had a record before that called “Super Sporm.” I don’t know if you know the song “Rapper’s Delight,” towards the third verse the guy says “He can satisfy you with his little worm/but I can bust you out with my super sperm…” he’s referencing Captain Sky’s record “Super Sporm,” which was a big East Coast hit.

Daryl was on the road and I got to go on the road. I was a pyro-technician, and I think I was fourteen. And I met great singers there. I met Gary Loizzo, who was the keyboard player in Daryl’s band. He had multiple synthesizers, and I was really excited about that. This was before I bought my own synthesizer. I would say that that was one of the things that made me think, “Man, if I could get me one of those synthesizers, I could make music!”

When did you start going to The Playground? Around when “Fast Cars” came out (1983)?

A little before. I was out late at night much younger than I probably should have been…. You know the place had been called Columns, I guess because of the thick pillars in the room, and it was kind of a gay juice bar, but another one of my mentors, Craig Thomson, took over that and made a teen club.

They were spinning New Wave music? What were they calling it?

That was just the music. There were a lot of DJs playing stuff like that. Frankie [Knuckles], obviously, was at the forefront, but there was Mike Ezebukwu and Ron Hardy, and there were a lot of DJs playing good disco music mixed with soul and other things.

There was a man by the name of Herb Kent. Herb Kent created a show at the suggestion of his daughter called “Stay Up and Punk Out” because Black kids in Hyde Park were listening to the B-52s and other records like that. New Wave records. We got our punk rock glasses and so on and so forth, and we would go do these dances at basement parties in the middle of the night…. That was another big influence to me, because [Herb] was playing soul records, disco records, and New Wave records in the same [set]. You could hear Parliament-Funkadelic and Kraftwerk back to back. Open format—real open format. That was the radio. I’d stay up for that show. All of us as teenagers would stay up to “Punk Out.” Other mix show DJs started following suit.

You’d go to The Warehouse, which was the epitome of the juice bars. It was the top of the pile, because reportedly they put acid in the punch. I shouldn’t say because of that, but that was one of the reasons. It had a mystique about it. It was hard for me to stay awake late enough so I could sneak out at 1:00 in the morning and go to a party because it didn’t get good until two, and I remember a whole adventure around going to The Warehouse. The few times I got to go there before it closed, those were really exhilarating experiences. I had already made “Fast Cars” by the time I got to The Warehouse parties. I heard Frankie Knuckles spin and heard the music at those parties, it was just so seamless and so physical due to the size of the sound system that it was a different experience for me. That drove us to want to make different records—more records, and get better. I saved up a bunch of money and bought another synthesizer and started looking for other people to be in my band. People that were closer to the scene that I was trying to capture. And that’s how I hooked up with Jesse Saunders.

You got a job at The Playground doing lights?

Got a little gig doing lights, and the next thing I knew I was throwing parties. I had a group called I.S.E., Infinity Space Eclipse. A guy by the name of Vincent Sparks had started a youth group in the neighborhood to keep us kids out of trouble, now that I really think about it. There were several of us in I.S.E., and we became party promoters. We all went to different schools. We organized ourselves, rented a place… and threw a few parties. A party that we threw where we experienced success, we had an idea designed to help police the parties, protect them from fights, and attached to our own culture at the same time. The idea was we were going to have an IZOD fest. All of the “Punk Out” kids were wearing Izod Lacoste and Polo clothing. So we said “bring your ’ZOD and work your bod,” and the fee to get in the party was $5 if you wore anything IZOD and $10 otherwise. Now mind you, in 1981, the difference between five and ten dollars was going to the party or not….

It caught on like crazy. There were 500 people at our party…. We had an IZOD contest—gave away money to the person that had the most IZOD stuff on. Craig Thomson stole that idea, and the venue that we rented that night, and threw IZOD/Polo parties for the rest of that year.

Next thing you know, I was doing lights at The Playground and Jesse and I were hanging out after the parties thinking about music. We met Duane Buford, who played piano better than the both of us, and we started making songs. Jesse started taking some of the money from his DJing and he started buying musical equipment.

Did he have any equipment before you met him?

None to speak of. No music-making equipment. He had a piano at his mom’s house. His mom was a school teacher.

What was the first thing you collaborated on?

“On and On,” pretty much straight away. Well no, first he joined Z-Factor and we recorded “Fantasy,” “Secret Agent Eyes,” “My Ride,” a bunch of New Wave. Kind of a cross between disco records and Prince songs. Most of what became the Z-Factor Dance Party album.

Screamin’ Rachael sang on “Fantasy.” I found her hanging around Universal, but didn’t realize she was active in the punk scene and hanging out at Space Place. Her singing on “Fantasy” was one of the first times the South Side and North Side musical contingencies worked together. Rachel was so open to what we were doing, as experimental as it was. She was important in moving into clubs that weren’t gay and Black.

We couldn’t wait for my dad to get the Z-Factor record out. He was just taking too long, too long. Probably two months or so, two and a half months, that was too long for us to wait.

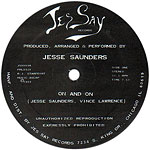

So that’s how “On and On” came out first?

Yeah, we kind of cloned “Fantasy” and put “On and On” out right away.

Same bassline?

Well yeah, a lot of it’s the same.

It was based on a megamix Jesse owned?

Yeah, there was a megamix called “Stars on 69” and it had looped a piece of some other record to make that bassline. And then it had all kinds of other stuff on top of it. “Funkytown,” this, that, and the other. And he had lost that record, so we wanted to go down that path and make a record that moved like that.

Why did “On and On” blow up so fast and inspire so many people?

We made the record and we started playing it in clubs and I got active about really promoting. We started Jes Say records and I became the marketing head for that company. It was my job to make sure that everybody knew about it. I covered every club in the city, with the help of Jesse because he had a car. We mapped out every club in the city, where all the DJs were, and made sure that everybody got a copy of it or at least we took a copy there and played it so they could go to Importes [Etc.] and buy it. We created this network of retailers where people who were interested in our sort of parties were shopping for their records. We really just hustled. A lot.

Our friends were also playing on the radio, so they were very excited about the fact that Jesse and I together had made this record. They really got behind it, and they were playing the thing sometimes three or four times per mix. Can you imagine a mix show where the back-beat record for the mix show was this one record? Then we had a bunch of beat tracks so they were playing other records on top of our beat tracks. They were really wearing it out, committed to the record. So it took off.

At the same time while that record took off, I was pretty active socially, and I just encouraged everybody. You know, “You should make one too. I made a record, you should make one.” My helping other people enjoy the same experience I had… ultimately led me to producing.

Did your father have distribution connections?

No, I ended up helping my dad. We had record stores like a paper route. We’d just go to the stores, show them the new records, they’d make an order. Because of the general limited supply, we could get stores to buy hundreds of records at a time. And because at some point we had multiple titles, it became a real business. I went to Detroit and created the same model there. After Detroit I went to New York, did the same thing, and then Miami. So we had four or five cities that we were selling records to.

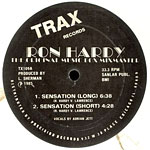

Jesse had signed a deal with Paul Weisberg, who owned Importes Etc., to put out his next release, so I went to the guy who owned the pressing plant and made a deal with him. I said, “Hey, let’s make some records. You know that we’re selling these things. I’ve got this idea. We’re gonna make records that are quick and easy to make, they’re fun, they’re not too complicated, because the kids at these parties, they just want to hear these tracks. And that’s what we’re going to call the label, Trax Records.” We agreed to make some records and get some masters in and we were going to split it. We were going to split the profits… and that didn’t really work out that way.

That was Larry Sherman?

Yeah. But really I didn’t care because I got to make all these records. That was kind of what I was in it for. Sometimes people ask me whether or not that was short-sighted, but I think that was part of my process. At the end of the day I’m where I’m at right now, and I’m not really in a bad way. Probably in a lot of ways I’m a lot better off than Larry.

So that’s how Trax Records got started?

Pretty much. I had been hanging out at Chicago Trax recording, and I had become a fan of Ministry who at the time were making all synthesizer-based records on a label called Wax Trax! I was enamored by the industrial movement and what was going on with it, so I said I want the label to be black with white text. And the name Trax, I don’t want it to be in the center, I want it to be off to one side on an angle. And I want the type to be really bold and hard print because I want it to be easy for the DJ to read what record they have. In the dark, even. And that’s how the logo design and image for the label started. I had previously designed the logo for Jes Say Records, wrote that one by hand. I’d hand-drawn a few fliers for some parties. I just loved art.

You said you went to Detroit. Were you aware of what was going on there with Juan Atkins?

Cliff Thomas, at Buy-Rite Records, we found him, and we found the record pool. We serviced Buy-Rite and we serviced the pool, and we would drive up for a party here and there but really knew nothing about it. Apparently Derrick [May] was coming down to Chicago and going to The Music Box, so he was very much aware of us and what we were doing, but we were oblivious. We were in our own world, making records every week.

You got writing credits on a lot of Jesse’s tracks, like “Funk You Up” and “Real Love.” Was that for the lyrics?

Yeah, mostly…. I [also] wrote Dr. Derelict “Under Cover.”

What year did Go Wild Rhythm Tracks come out?

That was ’84. That was when I started working with Marshall Jefferson…. Marshall was supposed to be the act. We only had enough money for a small amount of time, and we really didn’t have a sequencer to connect the 808 to any keyboards, so we just made a record that was 808 and DX-7, only a few patterns at a time per track, and then that was that. We made the best record we could given the circumstances. We only had a couple hours. Marshall wrote that label with his hand. A Sharpie for the big text, a ball-point pen for the small text.

Also, you worked on Ron Hardy’s “Sensation”? There’s a version on some old mix tapes where there aren’t any vocals and the synth stutters and pans. Is that from the same session?

Mmm hmm, it’s all from the same session. I did all the edit work. I was really really into The Latin Rascals and Arthur Baker and I had learned how to stutter edit. We’d cut the section of the song up into 16th notes and then insert blank pieces of tape. It was like this little experiment.

Can you tell me about your role in “Love Can’t Turn Around”?

Lyrics and melodies. I’ve told the story a few times about Farley [“Jackmaster” Funk] and Steve [“Silk” Hurley] being roommates and I don’t know if they were working on the record together or what. They had this falling out and Farley said, “I’m going to make this record. Steve was going to do Isaac Hayes’ ‘I Can’t Turn Around.’ I’m going to make a different record. Vince, call it ‘Love Can’t Turn Around.’ Write it today.”

So I wrote this story, “Now this is how it started/my dreams all broken hearted,” because there was this girl I wanted to date and she just really wanted to be friends. We were trying to find a singer, and I’d just recorded with this guy Darryl Pandy. Rumor has it that Darryl played the Cowardly Lion in the Broadway musical The Wiz. He had this big, bellowing voice and he could get right to the church nitty gritty. He was a good ad-libber. So we brought him in and he killed it. He just killed it. The performances were great, everybody was excited. Farley and Jesse released that record on some offshoot deal with Rocky Jones. They did a great job of getting it over to the UK. The rest is history from there. I was really moving in my own direction at that time, so other than the sessions, I really didn’t participate….

It seems like the UK picked up on the Chicago scene really fast. How did that happen?

J.B. Ross, Larry [Sherman], and Rocky [Jones], together with a guy named Peter Katsis, went to MIDEM, the international music licensing conference.

Then you were signed to Geffen Records?

That was ’86. I had been hanging out at Chicago Trax Recording. I’d been sitting in on these Ministry sessions, listening to Trevor Horn’s work with Grace Jones and The Art of Noise and Herbie Hancock’s “Rock It,” and I made a record that was one-hundred percent Fairlight synthesizer. I started getting it played around the North Side clubs. Peter Katsis and Jeff Kwantinetz threw the Midwest Music Conference…. All these A&R people from big record companies were coming into Chicago. I was just bound and determined to make a partnership…. So I met some people from Geffen…. At the time, I didn’t want to leave [Jesse]…. and they said, “You know what, we’ll give him a deal too.” And they signed us both.

So what came out of that deal?

I made that record [pointing to wall] “Sample That!” by Bang Orchestra! and I spent two years recording a bunch of other stuff that they didn’t understand that never came out. Jesse released an album that had “Real Love” and a bunch of other songs moving in a different direction, and that was pretty much the sum of that. We toured a little bit. I guess at the time they didn’t really realize what was going on. We didn’t realize what was going on, that we could have taken our movement and really expanded upon it. It was a learning experience for us all. We didn’t have any manager, or people like that involved, so we really just didn’t get it.

When did you decide to start your own company?

I want to say ’89. I was off Geffen and I started making indie records again. I had built a small studio and just started making records for myself and other people. I wouldn’t say I decided to start a company, it just kind of happened. I went to work.

Can you walk me through the nineties?

It’s a blur, back and forth to the UK. I worked on CCP, The Swans, converted Taffy’s “I Love My Radio” into a record that could be played in the UK. Radio went off at midnight in the UK and the hook said, “…my guy the DJ after midnight” so we had to change that to “the DJ up ’til midnight.” We hardened the mixes a little bit, made them a little more house-friendly. I got a chance to work with a bunch of great people at a bunch of great studios all over the world…. I worked with Daniel Miller, who is the president of Mute Records.

I think that was my college…. I learned music production from the best of the best all over the world…. They wanted me to incorporate the thinking that was present in our Chicago jack tracks music with the music they were making….

Photo by Steven Koress

This one’s now my third actual full-on facility…. We’re doing music for The Oprah Winfrey Show, a lot of television and radio commercials, remixes of big pop stars: Beyoncé and R. Kelly.

The sound that you pioneered in the eighties has become part of the mainstream, part of our culture, but it seems that you like being the guy behind the scenes.

Yeah, I do…. Initially, I liked helping people…. I wasn’t that great a singer, and honestly, I was pretty introverted…. Sometimes it’s not even about the glory, because I’ll make records that I don’t even put my name on, just because I want to see something out. I like this stuff [the studio], the other stuff that came along with it.

What do you think of the scene today?

I don’t think it believes in itself like we did. People told us that the music that we were making was not music. “What the heck is this junk?” And the “junk” took over the world.